Our Approach

Lambs. Our lambs are born beginning in early- to mid-March, when winter is beginning to relax its grip, so that they can begin to graze when spring grass is growing at a furious rate – just as Nature intended. This means that they’re too small for the Easter market, but they aren’t being raised indoors all winter long, never getting a chance to graze under the sun. We don’t allow our livestock access to our streams; this helps protect the Chesapeake Bay from excessive loadings of nutrients and sediment. Instead, they drink from groundwater-fed stock tanks. More information on our sheep is available here.

One of our groundwater-fed stock tanks

Chickens. Our chickens are fed a high-quality vegetarian layer mixture, supplemented by free access to chicken grit, ground oystershell (for strong eggshells), as many bugs, worms, or slugs as they can capture, and trimmings/thinnings that we provide from our (organically-raised) vegetable garden, in addition to scraps from our own meals. The chickens are allowed free access to the pastures during the day, where they also eat grass and weeds, as well as the occasional lizard or frog (chickens being omnivores by nature). A diet high in green leafy vegetables (or leaves from our vegetable garden too full of bug holes to be appealing to humans), along with grass, gives their yolks a dark-orange color. Most of our flock consists of two breeds of chickens, both of which are dual-purpose (meat + egg) breeds: Welsummers, which lay dark chocolate brown eggs in “large” to “extra-large” sizes, and Ameraucanas, which lay light blue-green eggs in large sizes. We also have a cross between these two breeds that lays olive-green eggs, as well as some red sexlinks and Delawares, which lay a more familiar light brown “large” to “extra large” egg. More information on our chickens is available here.

A young Welsummer hen (three months old, not yet laying)

Our Practices

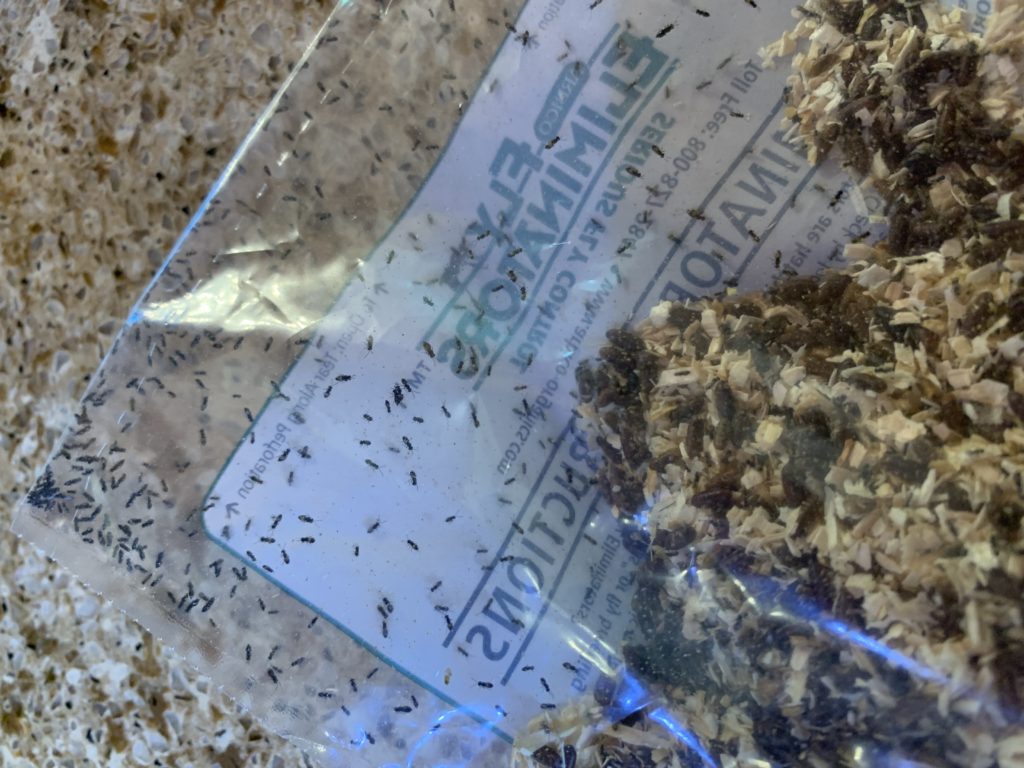

Concern for the environment. We try to practice organic farming methods to the maximum extent possible, although our farm is not certified as organic. We keep our fenceline clear of weeds by mowing and by using a weedwhacker, rather than by spraying Roundup (glyphosate) as is common practice with many farmers. In our flower gardens, we use horticultural vinegar to kill weeds in our brick walkways. It makes the gardens smell like salad dressing, but it’s effective! We hand-pick Japanese beetles from our vegetable and flower gardens each morning for a special treat for the chickens. Flies in our pasture and barn are controlled with predator wasps – gnat-sized flying wasps that parasitize flies.

A bag of predator wasps, ready for release

Nonlethal approaches (such as row covers) help our young eggplants, peppers, tomatoes, and cabbage family crops avoid the depredations of pests such as flea beetles or cabbage loopers, and collars of aluminum foil help keep cutworms from killing our vegetable plants. When absolutely necessary, we will spray our vegetables with organic preparations (such as Spinosad and Bt) to control pests – but we only use products that act specifically on the pests we have identified, with negligible ecotoxicity, and (equally important!) that won’t harm pollinators such as honeybees. Animal manure is composted (along with kitchen waste, such as coffee grounds, not suitable for the chickens), and is used to fertilize our vegetable gardens. We do not allow persistent herbicides on our pastures or hayfield such as Grazon/Milestone (aminopyralid), or on any hay we purchase. This herbicide is excreted in animal manure – rendering the animal manure toxic to susceptible plants for a full year (or more) after application of composted manure to flower or vegetable beds or pastures.

One of the sunflowers planted to support pollinators

Concern for both human and animal health. We do not ever use antibiotics or hormones as growth promoters in our animal feed – ever. We do reserve the right to administer antibiotics or deworming agents to ill animals, but only when needed, never routinely; in such infrequent events, we will exceed any USDA “withholding” requirements before sending a lamb to market or collecting eggs for human consumption. Unlike routine use of antibiotics as growth promoters, occasional use of antibiotics for therapeutic purposes has not been associated with the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. We feel we would be poor stewards of the animals dependent on our care if we denied them antibiotics or deworming agents when medically necessary simply to be able to market them as “organic”.